History of Landscape II

- Description

- Curriculum

- Reviews

The 16th Century Landscapes

Garden Style and Form

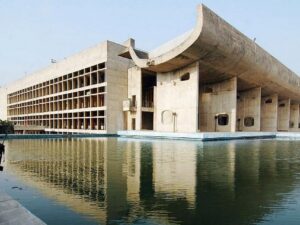

Gardens held a central place in the history of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century European art and architecture.

Two distinct types of gardens developed during this period. In the seventeenth century, defined as formal Geometric Layouts or Baroque gardens—were designed according to exact mathematical rules and strict symmetry and planted with artificially trimmed plants and trees. In the early eighteenth century, the desire to make gardens more “natural” resulted in the development of the Landscape Gardens, based on irregular, undulating forms. Each garden type was the result of a different set of aesthetic values and philosophical ideas. What distinguished the Baroque garden from the earlier Renaissance garden tradition, even though it consisted largely of the same elements, was the concentration on dynamic spatial features and splendour. Typical is the Baroque garden’s enormous scale, complexity of composition, richness of ornamentation, and sweeping vistas.

The design Principles, that involve Landscaping in the 16th and the 17th CE revolved around

Unity and Continuity: Unity deals with one-ness, by fitting together of different parts to result in a ‘harmonious whole’. It is achieved by using components with same/similar physical qualities. The uninterrupted transition from one part to another by balanced repetition of noticeable components is termed continuity. Both ‘inward-looking unity’ [unity within the garden] and ‘outward-looking unity’ [unity of the garden with its surroundings] have to be maintained in the landscape.

Accent: The noticeable difference in the physique of components from its surroundings that draw attention to itself is termed accent. The accent breaks the monotony due to unity as well the repeated accents turns to be the basis of continuity and total unity of the landscape.

Axis and Focalization: Axis is the imaginary line on either side of which, the design elements striking a balance each other. In big landscapes there may be more than one axis. Focus is termed the climactic point of the design on which all other components lead the attention of the viewer. In a formal garden, the focal point is often the terminal feature at the end of the axis or the crossing of two axes. In an informal design, the axis is not necessarily a straight line. The components are deployed in a balanced way to act as a vision which lead to the focal point.

Balance: The visual equilibrium of the design components in either side of the axis is termed balance. In symmetrical balance, a central axis utilizes with an exact repetition of components on its either side. Asymmetrical or informal balance is achieved through the employment of harmonious features or areas of equal attraction on either side of an unstressed axis.

Scale and Proportion: The scale denotes the relative size of the landscape components. The proper relationship in scale between the landscape components and the whole landscape to its surroundings is termed proportion. When plants are the landscape components the designer should be prejudicial on the change in scale happened to them on growing up.

Linearity: Line may be perceived as the junction of the adjacent parts in the garden landscape. It could create control pattern of visual movement and attention. That is, the curvy, informal Lines’ may retain the visual continuity of the components one after another whereas straight lines emphasize a particular component on which the vision may get struck.